What is ideology but a set of beliefs or philosophies that someone holds at a point of time and is 100% shaped by our social environments – where we live, how we live, based on our politics, our families or friends, our shared and individual social norms and experiences. Although we aren’t born with it, but wow does it have an important role in shaping our present and our futures (and now our planetary pathways too)!

A big influence on how we perceive major risk issues – be it the environment/climate change, technological change, war, economic troubles and social deviances – is determined by our ideologies and how we think individuals and societal institutions should function. Risk is a big factor in what decisions we take (for the current and future) and our culture and ideology more than influences what we see as being risky.

Given that climate change is a big issue where future wellbeing is determined by current risk reduction, it becomes necessary to understand how our own behavioural biases are preventing us from making overall better (or optimal) decisions in the present. A very interesting preview for what is to come (in reacting to climate impacts) can be seen with our current response in the ongoing pandemic! This blog post is a result of a frequent discussion we have, on why people don’t respond as easily to climate or risk information and why culture and communication have a huge influence on what is seen as a social and individual priority.

Before we start talking about the past 8 months of 2020, here’s a quick summary of what is documented in academic literature as risk- and cultural- biases. Based on culture theory there are three distinctive patterns of social relationships – hierarchical (highly influenced by social norms and social structures of society), egalitarian (value strong equality and reducing inequality among people based on wealth/gender/social class etc) and individualist (support decisions best for individual, i.e. more freedom and a more self-centered view).

VASU: These cultural social relationships are the basis of what forms our ideology and how our distinctive culture can influences our views under high risk scenarios like climate change or the pandemic. Unfortunately, the influence of scientific facts and knowledge is subsequently reduced in the face of these biases and social influences. If it wasn’t the case, we would have likely solved societal problems like climate change and pandemics already!

According to cultural theory, our social relationship biases influence our priority on things like environmental risks (climate change) or even health risks (pandemic response). For instance, if you were more egalitarian in nature, you would see environment/climate change as being more important as opposed to risks posed by economic troubles. Hierarchical society is driven by following social rules and maintaining social norms – anything that deviates from this is seen as a risk. And individualist societies are more likely to perceive risks on things that restrict their personal freedoms (think America and protests against wearing masks).

Even as I write this, the tweets on my twitter timeline are telling of the polarization of the pandemic and other societal problems like climate change. Some argue for it, others against it. Some say its getting better, others say it’s getting worse. In some countries COVID numbers are rising, in other countries the numbers seem to be falling. Due to a globally connected society, I am able to access the same information as someone from around the world – allowing us to truly educate ourselves and keep informed. And information can be a direct influencer of what we believe to be a risk – but whether that information is reliable in this age of social media is a highly debatable topic. Whether it is even reliable from a government can be highly contested – as seen in the early days of the pandemic and on how certain governments handled COVID disclosures. As one study puts it, even in straightforward global issues like climate change (which has full scientific agreement),there is still ongoing debate on whether it is urgent and if any changes need to be made (even as we lose valuable time) because cultural norms tend to encourage short-term thinking and reinforce our biases.

This brings me to what we hear around us and how we process this information to fit within our worldview – what are our friends, family, colleagues, politicians, policymakers etc. actually saying and how does it reinforce our idea of a response in the face of a societal threat? As humans we constantly look to reinforce our beliefs and our way of life – we like the status quo and nobody likes having their world views questioned or critiqued. This is known as confirmation bias and is documented in everything we do! We want to reinforce what we believe in – same goes with the pandemic and how we perceive it, with a little help from friends/family/peers of course!

Here’s why social circles matter and based on your social relationship biases (hierarchical/egalitarian/individualism) one tends to filter the information in a manner that fits within ones worldview – influencing whether we perceive the pandemic as a threat or not! Sadly, climate change is a threat multiplier and social problems seen in this pandemic (job losses, housing instability, food insecurity, mental health issues etc) are only going to get worse with more climate disasters – making our confirmation bias even more likely to kick in and influence our reaction and our social situation (better or worse).

VASU & MATT: An evident example of this in our experiences has been when it comes to social gatherings. In Canada (where we live), indoor social gatherings are highly discouraged because they are a major cause of COVID spread – with limited ICUs and extended strain on healthcare workers – there is a social stigma on those that go ahead with social gatherings, especially during a lockdown. It is socially bad to meet others in a setting that will enable a greater spread (or is inconsistent behaviour to the rules) – and because it is socially unacceptable, people are less likely to do it. In fact it encourages a sense of social repercussion for people that do take these actions, like the recent hypocritical case of Ontario Finance Minister who was away on international vacation as the provincial lockdown that started in December (people to stay home and avoid social gatherings or travel). This caused a public outrage and has led people to demand his resignation – a consequence of how social pressures can also evaluate leadership in times of crisis. But social pressure also depends on what sort of issue is taken seriously and prioritized by a society – economic recovery? those affected? the environment? social norms? Only time will tell what is truly important to a society, but in the meantime we end up losing lives as collateral in a totally preventable crisis.

In India (where my family lives), social gatherings have always been a big part of society (even more so than other parts of the world). Even in a pandemic, social gatherings like weddings and family get-togethers have continued, although at a limited capacity than before. But the social stigma doesn’t exist for those that hold these events, rather for those that do not attend them. As you can see, each place has a different kind of risk perception for the same problem and it is most definitely influenced by the social pressures and social relationships among people. Now you can understand how hard it is to convince people that climate change is an important (social, financial, physical and mental) risk -there is no single global agreement or definition for risk (even as we live through a global pandemic)!

MATT: If we were to look at these global events – whether it be pandemic or climate change – based on solely on what information they provided (not always through a social lens) and reacted to them accordingly, the solutions would be straightforward. New Zealand has been an interesting example of controlling the COVID spread based on its quick and efficient response, evolving guidelines based on scientific expert advice, clear leadership and effective rule following by its citizens. Although it is a small nation, we can all learn a lot when it comes to responding to such crisis – better knowing our cultural biases, (re-)evaluating our risk perceptions and understanding how our social spheres influence our reactions to threats we perceive (which might not always be a good thing).

Leading by example in the pandemic situation is seen by those that are well informed (based on scientific information and not social media), exemplify consistent leadership behaviour (evolving with the situation and not giving in to traditional management approaches/social pressures – a good example is companies that have changed back to working from home for employees after seeing a second wave), concern for others as opposed self concern (not meeting as many people that you usually would/keeping a closed bubble/taking precautions with vulnerable people).

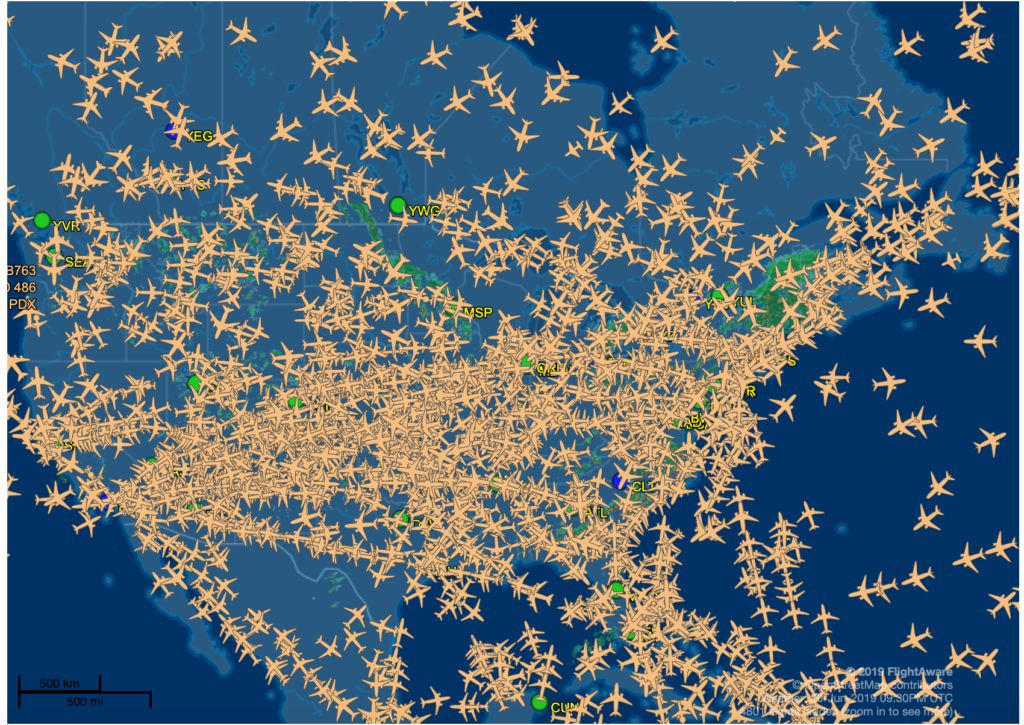

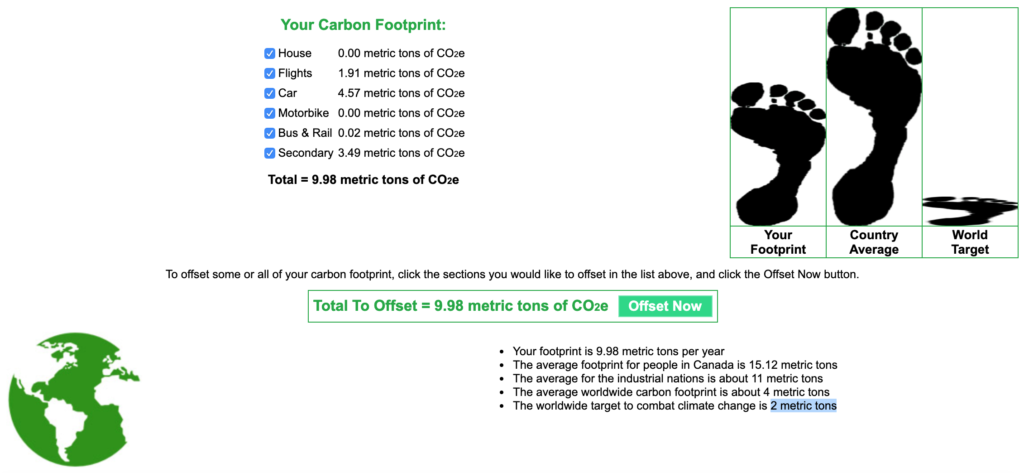

Nobody likes making sacrifices (after all it wouldn’t be called a sacrifice if we did like it) – but that is what real leadership and response to rational information is all about. It is making decisions that might not be popular or might go against the status quo – for the greater good (which is obviously a very subjective thing based on where you live). Fortunately, in Canada the greater good is seen as the state of the health, rather than the economy (and we are fortunate to have this frame of mind) – however, this is also a short-term problem that has a visible impact from political decisions. But when it comes to climate change, these decisions have to be made again (and may not have a visible present day impact) and sometimes the economy ends up winning. If we were in fact a leader, it would mean making sacrifices in the present (transitioning away from fossil fuel industries) to allow for wellbeing in the future (a safer environment for future generations): A lesson from the pandemic as we live it – because as nice as it would be to meet our friends and family across the world (short-term thinking), it doesn’t mean that we should (long-term thinking) because it might mean exposing them to the virus. To us, this is what the greater good is all about!

VASU & MATT: As more climate impacts occur – some of which may come in the form of new and deadlier pandemics – our social and individual resilience might try to get us back to our old normal, but sometimes we need to go beyond normal to really tackle the problem in a way that prevents it from occurring again. Risk perception and risk taking is good in certain contexts (career/social situations etc.), but the real (bad) risk happens when we as a society cannot come together to address a future where our livelihoods, our societal structures and our sense of climate safety are gravely threatened just because we did not listen to the warning signs and gave in to our biases.

Here’s a great video that explains (in animation) why facts don’t work and why ideologies need changing: